John Ariel Crosby

(1909 - 1972)

Hello, Everyone,

I am Paul Harvey Crosby, the sixth and youngest child of John Ariel Crosby and Maxine Virginia Harvey Crosby. My father, my siblings and I, are all direct descendants of Simon Crosby, who immigrated from England to Massachusetts nearly 400 years ago.

Herein, I would like to tell you the story of our branch of the family, most of which has taken place in the 1900s.

*I am the 9th great grandson of Simon Crosby. Simon and his wife and child, and a yet-unborn child, made the very perilous journey across the Atlantic in 1635 to reach America.

My grandparents are Clarence Wallace Crosby and Teresa Levice Day Crosby, and Lelburn Curtis Harvey and Mabel Catherine Wood Harvey. They lived and reared my parents mainly in and near Glen Ellyn, Illinois, a small western suburb of Chicago in the first 30 years of the 1900s.

My father lived at first in Zion, Illinois and later, Glen Ellyn. For about five years, my father lived with his parents and six siblings and in and near Bartle, Cuba, when he was between the ages of about two to seven years.

His mother and sister died of malaria in 1916 and 1917, respectively, in Cuba. They are buried, presumably, in or near Bartle.

Soon afterward, my grandfather, Clarence, fled Cuba with his six sons, due to a bloody political revolution going on in 1917. They returned to Zion, a small town near Glen Ellyn.

My parents met at a mutual friend’s birthday party in Glen Ellyn in about 1925. Their meeting was one of extreme fondness for each other. My father was 15; my mother, 12.

I say “extreme fondness,” because, as my mother explained, my father “was at my house the next day.”

They sporadically dated others during the next several years. But on November 6, 1931, they were married in a small wedding, in a quaint English Tudor style house in Glen Ellyn.

They went on to grant birth to my five siblings and me: Julia Day in 1932; Nancy Virginia in 1933; John Ariel, Jr., in 1935; "Living" in 1937; "Living" in 1940, and finally, me, Paul Harvey in 1950.

Julia Day and John Ariel, Jr., each died in infancy due to a disease involving a thin and perforated intestine. Julia Day lived about a year; John Ariel, Jr, a few months.

Nancy Virginia died in 1994, at age 60, due to a stroke.

My three siblings who lived to adulthood each blessed my parents with eight adoring grandchildren.

Nancy, four grandchildren; "Living", two, and "Living", two. I have never married, and so I have had no children.

Of Nancy’s four children, only one survives, a daughter. The three others have died, the youngest at age 20. The others have died of various illnesses, all very tragically.

My father was born December 21, 1909; my mother, July 21, 1912.

I believe most people nowadays would consider their marrying so young was, at best, a very risky venture.

The stock market had crashed in 1929, and the Great Depression and jobless rate were at or near their peaks when they married.

My parents and my mother’s brother and sister-in-law all lived with my grandparents in Glen Ellyn. The weather was very cold and inclement, with plenty of snow.

My grandmother, alone, had an income. She was a Christian Science practitioner, and fortunately had quite a good income. The rest of the family was unemployed.

My grandparents decided a change was needed, so they told the family they had decided it best for them all to move to a remote area in northern Wisconsin and buy an inn they knew about, and operate a bed-and-breakfast.

They did just that, but made one fatal oversight: tourists came only in the summer, during warm weather. The winter was too cold.

Hence, no business.

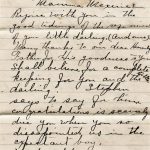

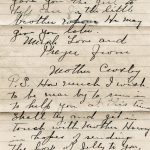

My father told my mother and the others that he would walk his way out of the wilderness and keep going until he found a job.

So he did; he landed a job at a filling station in Eau Claire, Wisconsin. He and my mother communicated by mail during their separation, and in the Spring, he returned to bring my mother to Eau Claire.

He worked 12 hours or more each day, and earned about $20 per month. He had a half day off on Sundays.

The whole family returned to Glen Ellyn in a few months, and my father got a job with the Sears Roebuck Company in Chicago. Life was peaceful, and my father built a house single-handed for his branch of the family.

When World War Two broke out, my father was exempted from the draft and military duty because he was married with three children. So he was assigned as a final inspector in a warplane plant in Chicago. Later, he worked for the Electromotive Company, a manufacturer of train locomotives.

But my mother and father were concerned about bringing up their children in such a large, urban area, and an infamous gangsters’ headquarters.

My Uncle David and his wife, Eleanor, settled in Portland, Oregon after the war, and persuaded my parents to move out to the Great Pacific Northwest.

My family, minus me, since my time had not come yet, embarked on their westward journey in 1947.

Hauling quite a long trailer, they traversed two-thirds of the continent, stopping to visit my father’s Uncle George and his wife, Minnie, at their wheat farm near Hardin, Montana.

My parents were impressed by the way George and family could be so contented with what most people, even in 1947, would consider primitive living conditions. They were so resilient and hardy, yet happy.

An outhouse; a well for water; blazing hot summers and bitter cold winters, during all of which they had to struggle to minister to the needs of the farm, and simply surviving.

Little if any insulation in the house, and absolutely no air conditioning.

All surrounded by a barren, stark, forbidding landscape.

I wish I could have known George and his family. People like them make me feel ashamed of myself sometimes for considering small matters problems.

After a week’s visit, my family moved on to Oregon, to start their new life.

This next step was not so easy, mainly because my parents had different visions. My father wanted to “homestead,” and live rather like Uncle George and his family. He wanted to buy a totally unimproved property west of Portland, while continuing to live in the trailer.

To want more was to be weak of spirit.

To my mother, such a rough life wasn’t suitable for rearing a family. She wanted to buy a small farm east of Portland, which had accommodations something like standard for 1947.

They settled on my mother’s choice, but my father was never really happy with it. He longed to do something more challenging and original; more “from scratch;” something more “Crosby.”

Still further, he felt certain he had the genius to become a successful inventor, like his father and his older brother, Steven.* He had unwavering faith that doing something great, independent of anyone else, would eventually bring us all great prosperity, if only his family had faith in him.

These differences between my mother and father made for an unhappy life for them, living on our farm.

I was born in 1950, and we left the farm in 1953, so I have hardly any memory of the unhappiness that engulfed the rest of my family.

But my mother and brother and sisters carried wounds from those six years from then on.

Boredom; isolation; back-breaking hard work, and a turn-of-the-century house with no present-day comforts, much like George’s and Minnie’s.

My father made an effort at making a living, but he later told my mother, “my heart just isn’t in it.”

My mother found out later that my father had only paid the interest on our farm’s mortgage, but nothing on the principle. He had never wanted to own it.

Meanwhile, a neighboring farm family was using their property to operate a ceramic drainage tile factory.

This caught my father’s eye, and his interest.

My father had great pride in his father’s and brother’s successful inventions.

I believe he continually watched for ways in which he could take an existing tool, household item, or manufacturing process, and make them better or even obsolete,

by coming up with his own, better idea.

Further, I believe he looked for ways in which he could excel even in things he otherwise disliked, like our farm and its output, its products.

We raised chickens, and he developed such a good feed for them that a restaurant in Salem sought him out to sign a contract to supply at least some, if not all, the chicken they needed for their menu.

He also developed a high-quality type of grass which yielded seed from which lawns could be planted. He was very proud of his “Chewing’s Fescue.”

However, none of this made my brother and sisters happy, and the fields of grass made my mother deathly ill with asthma.

Both my parents received teaching from their earliest years that doctors and medicine were evil. And even though my mother lay in bed nearly dying and gasping for breath, my father had decided to simply wait for her to get well.

By this time, my mother had become so desperate in her pleas for medical help, that my father took her to see the only doctor nearby.

The doctor ordered my father to get my mother away from the grass, or else prepare to lay her to rest forever, within a short time. And so, it was off to Uncle David’s and Aunt Eleanor’s home in Portland for my mother and me to stay several weeks until the grass season, and the grass pollen, were spent.

At some point, my father decided to quit farming, and he instead went to work for the neighboring family who operated the ceramic drainage tile plant.

He actually loved this work, I think because it offered him some inventive possibilities. He thought he could make a better drainage tile, but first he needed to learn the business from our neighbors.

Things went smoothly, and soon he was hired by another brick and tile plant in Forest Grove, west of Portland.

He succeeded at producing a superior tile, and he brought the plant back to financial health, from where it had been, about to collapse.

The local newspaper even sent a reporter and photographer to interview my father, and to tell the story of his success. A major story about him appeared on the front page.

Our family was much happier living in Forest Grove, and we were starting to recover psychologically.

Unfortunately, the owner had decided to sell the plant, and my father was fired by two co-workers who planned to use his formula to run the business profitably themselves.

The business did go broke a short time later.

At this time, my father was 47 years old, which was considered much too old, in 1957, to ever find a desirable job or livelihood again. And my father remained under-employed for the next three years.

We were desperately poor.

We had very many moves from one place of semi-employment to another. By the time I was 10, I had attended eight schools.

We moved finally to live with my sister, Nancy, and her husband, in Portland. My parents’ bedroom was in the attic of the four-story house, and I shared a bedroom with my nephew.

I believe my father still hoped for success as an inventor, but his time to expect worthwhile employment by someone else was over.

Then, he received an invitation to interview with the State of Oregon, based on the skill he had gained while running the electrical power plant decades before, at Wheaton College in Illinois.

The job he was accepted for in Salem, involved providing, among other critical necessities, electrical power to operate, and most importantly, keep locked, the cell-block doors within the state penitentiary.

I believe my father rather favored a livelihood of semi-employment because it allowed him to use half his time trying to invent the truly “golden,” invention. He was a very intelligent man, but with a wife and a nine-year-old son still dependent on him, he needed an income most of all.

He nearly declined the interview, but my mother persuaded him to follow through.

In January, 1960, he, my mother and I moved to Salem where his new place of employment with the state was located. We had a whole house of our own again for the first time in about a year and a half.

I entered the fourth grade, mid-year, at Richmond School, and learned there was more to life than misery and desperation. I loved school in our new home.

And in September, 1960, I went on to fifth grade, where I was able to stay the entire year, for the very first time since I had begun school.

We moved two more times, within Salem, but each of those moves were of my parents’ choosing, and provided us, more and more, a happy way of life. My father’s job with the state allowed him a good deal of opportunity to exercise his inventive talent.

My father died November 27, 1972, while still living happily in Salem. He was 62.

My mother lived on happily also, outside of grieving the loss of my father, until her own death on April 22, 2010, at age 97.

She never remarried.